An overview of how blockchain is being used to improve food and agriculture supply chains around the world.

The blockchain community has come a long way over the past couple of years. We have moved from a focus on cryptocurrencies to a wider understanding of different ways we can leverage blockchain technology across industries. I’ve counted more than fifty different initiatives focused on food and agriculture around the world that are doing more than just raising funds through an ICO (Initial Coin Offering) to build a platform. Here are the six main ways I am seeing blockchain applied to food and agriculture supply chains.

- Traceability

The most common use of blockchain in food and agriculture supply chains is to improve traceability. It enables companies to quickly track unsafe products back to their source and see where else they have been distributed. This can prevent illness and save lives, as well as reducing the cost of product recalls. Information being collected and the stakeholder groups involved varies based on the needs of the groups behind each initiative.

The IBM Food Trust initiative started with their collaboration with Walmart China and Tsinghua University, and has grown into a global consortium that includes big names companies such Dole, Driscoll’s, Kroger, Nestle, Tyson, and Unilever. Frank Yiannas of Walmart has said that the improved data traceability provided by the IBM platform reduced the time it took to trace a mango from the store back to its source from seven days to 2.2 seconds. That reduction in time enables companies to identify contaminated supply chains and recall affected products before they are consumed and cause illness.

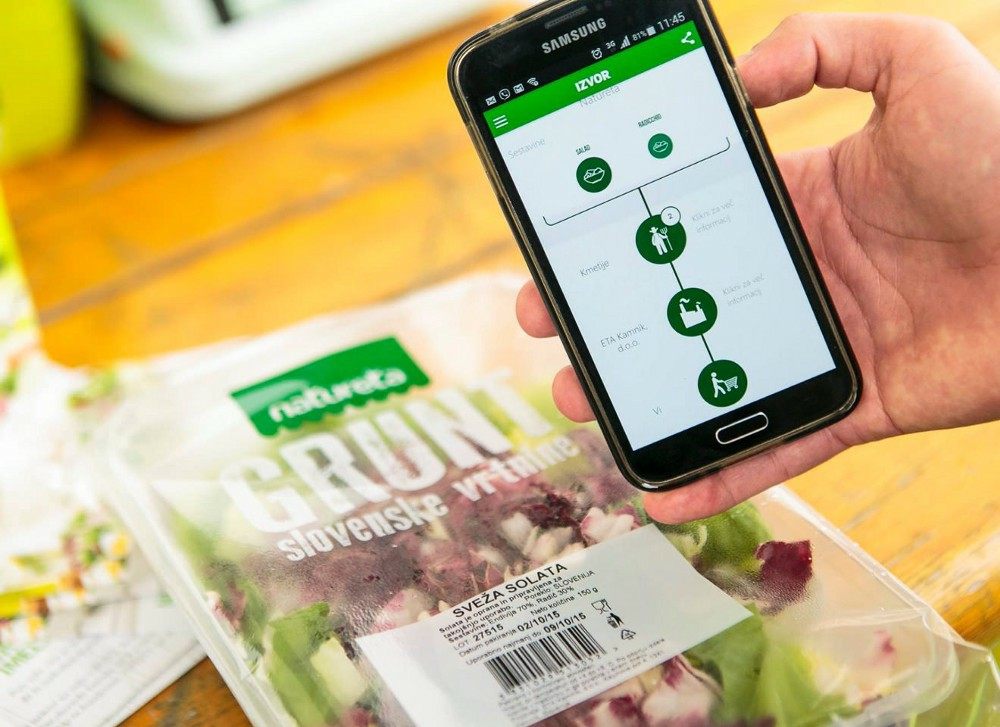

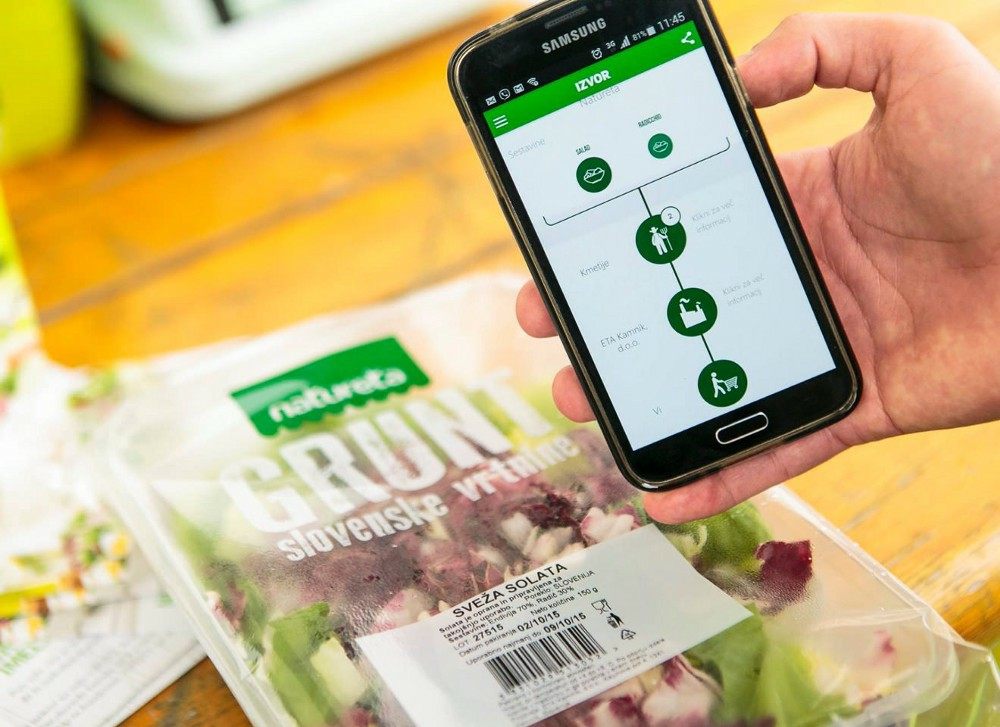

OriginTrail is a Slovenia-based company that is getting attention around the world for their traceability initiative. Transaction processing and storing blockchain data to trace products can be expensive. OriginTrail has found a way to store only “fingerprints” of data on the blockchain, which founder Žiga Drev says reduces the cost to only cents per item, or even a fraction of a cent when the fingerprinting is be done at the batch level, as for low cost FMCG (fast moving consumer goods), such as beverages or prepared foods. The team also understands that systems do not operate alone, and has created the Trace Alliance, a consortium of companies who are using blockchain for supply chain traceability. Members include Deloitte, HalalTrail, Oregon Tilth, and Phy2Trace. (Full disclosure: I am a member of the Trace Alliance through my company, Cultivati.)

Viant is a supply chain traceability focused subsidiary of Consensys, which is making global waves for using blockchain to address many different challenges (civil.co is a platform for trustworthy journalism, uPort is an identity management platform, Ujo is a platform for musicians to share content and connect directly with their fans). Viant has partnered with in Fiji with WWF and Traseable Solutions to track albacore tuna caught by Marine Stewardship Council-certified fishing company Sea Quest Fiji. Automatic Identification System (AIS) transmitters were installed on their vessels and operate continually to track and monitor fishing activities. Fish are tagged with a sensor when caught; that sensor interacts with the AIS transmitter to record both the time and exact location. The location data confirms that the fish were caught in a place where fish stocks are not over-exploited.

Belfast-based arc-net has incorporated DNA information into their blockchain platform. They begin by taking a tissue sample of an animal early in the supply chain and uploading part of the genetic code with other information being stored. When importers and others further along the supply chain receive the meat they can then test a sample and confirm that the DNA matches that which they were expecting. They’ve also made headlines for a whisky blockchain with Scottish distillery Ardnamurchan, which includes information on the water and grain used in production as well as the identity of the distillers who made the whisky.

Provenance is a London-based blockchain company with an overt social and environmental impact focus. Company founder Jessi Baker recognized that customers want to understand the social and environmental impact of their purchases. Provenance provides transparency for both food and clothing companies, allowing customers to not just learn where their dinner or new jacket came from, but also confirm that the people who helped make the product were fairly compensated and that it was made in a manner that is environmentally responsible.

Chinese commerce giants Alibaba (parent of Taobao) and JD.com are using blockchain-backed traceability to improve consumer confidence in the authenticity of food products in an environment where food safety is an everyday concern for customers. Beijing-based JD.com started by tracking beef from Kerchin, a company in Inner Mongolia (a province in northern China), to customers in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. They’ve also worked with Australian exporter InterAgri and processor HW Greenham & Sons to track Black Angus beef from where it is bred and raised through to processing and transporting. Josh Gartner, VP of International Corporate Affairs at JD.com says that they are hoping to offer the same products to customers of JD’s new premium offline grocer chain 7FRESH as they continue to expand their offerings.

The BeefChain was founded by Wyoming cattle ranchers who wanted to know where their beef was being sold. The “rancher centric” platform tracks beef along the supply chain, and enables ranchers to recapture value from third party actors along the chain.

Blockchain is not the only technology changing the way things are done when it comes to agricultural supply chain data. What makes many initiatives noteworthy is how they combine blockchain with other technologies, such as IoT (Internet of Things), like the AIS sensors used by Viant’s partners in Fiji, or AI (Artificial Intelligence). This can be especially useful because it removes the likelihood of human error — whether deliberate or accidental.

Several companies in China are demonstrating different ways IoT can be used with traceability initiatives. ZhongAn Technology, based in Shanghai, has a platform called Bubujithat puts sensors on chickens when they reach a certain size. The sensors not only track the location of the chicks, it also allows customers to see how much they moved on a daily basis (think of it as an exercise and location tracker for chickens). Walimai has a sensor it places on baby formula canisters that registers when the canister has been opened. If a customer scans the QR code on a canister to learn about the supply chain they can confirm that the can has not been tampered with. This is especially important in a market like China, where food safety is a top concern of consumers due to multiple cases like the high profile 2008 baby formula food fraud food safety scandal, which caused a reported six deaths and resulted in kidney damage in hundreds of thousands of children.

There are many other traceability-focused initiatives. A few noteworthy ones include Ambrosus (formerly known as FoodBlockchain.xyz), out of Switzerland, which provides tracking for both the food and pharmaceutical industries; BeefLedger, an Australian beef traceability initiative focused on exports to the Chinese market; the Chai Vault, a UK-based wine initiative focused on verifying the provenance of investment-grade wines; OwlTing, founded by an ex-Google employee in Taiwan in 2010 to enable consumers concerned about food safety to buy directly from farmers; TE-FOOD, focused on providing farm-to-table traceability in emerging markets; and Zest Labs, another US company that uses sensors to collect data that enables companies to reduce food waste.

2. Commodity Management

Agricultural commodities are big business, and commodity managers have been plagued by data management challenges and payment time lags. Blockchain is enabling innovation that addresses these issues.

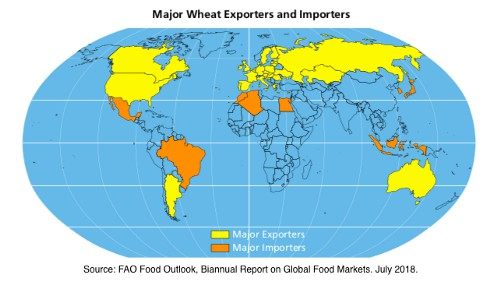

Australian company AgriDigitalprovides cloud-based agricultural commodity management services recorded onto a blockchain. CEO and cofounder Emma Weston says that she and her cofounders knew they “could create cost-effective, efficient and world-leading agri-commodity management and supply chain solutions that would have global impact” by using emerging technologies. In 2016 they completed the world’s first farmer to buyer wheat sale recorded on a blockchain; since then they have run pilots for food traceability and supply chain provenance, real-time payments, digital escrows and supply chain finance.

At the end of 2017, Rotterdam-based trading house Louis Dreyfus Co.completed its first agricultural trade using blockchain, for a sale of U.S. soybeans to China. Deal documents, including contracts, letters of credit, and government certifications, were all digitized, and data was automatically matched in real time via their blockchain platform, which avoided duplication and the need for manual checks. This reduced document processing to one fifth of the usual time and cut overall transaction time in half, from two weeks to one.

3. Marketplace Creation

One challenge for commercial food companies is sourcing quality ingredients in sufficient quantity. Farmers may not know who the big customers are or what end customers are looking for. Historically, intermediaries have controlled a significant percentage of profits. Digital marketplaces allow buyers and growers to connect directly, increasing the amount of profits that go to the farmers, and investors to invest directly into farms producing commodities and then trade on that investment.

Avenews-GT is an Isreali-based company that has created a trading platform which allows commercial buyers to find the growers who have what they need. Their first projects allowed coffee-buyers to find coffee growers in Rwanda, and cattle farmers in South Africa to find alfalfa to feed their animals, request a digital quote and manage payments all within the Avenews-GT platform.

For commodity traders, London-based Binkabi has created a commodity marketplace that reduces foreign exchange expenses and increases profits. Their Barter Block™ protocol groups opposite trades together for settlement, which improves the performance of each trade while keeping them independent of one another. It also allows bilateral trades to be conducted in local currencies on both sides.

While most wine industry initiatives using blockchain are focused on traceability and authenticity, VinX is a platform for trading wine futures. Wineries can receive funding directly from consumers, enabling them to develop relationships directly with their customers and reducing stress around the often multi-year gap between receiving funds and sales.

4. Data Sharing

Companies that buy or invest in agricultural products have an inherent interest in having information about the product before they commit to a purchase. This can include everything from salt and sugar levels in tomatoes, which would affect flavor, to crop health information, which can help banks and others predict whether a farm will be able to repay a loan.

California-based Ripe.io collects data from sensors, spreadsheets, manual surveys and other sources along the supply chain to give commercial buyers detailed information about product attributes. Their first project tracked tomatoes from Ward’s Berry Farm in Massachusetts that were destined for the salad chain Sweetgreen. Data points such as light, humidity, air temperature, tomato color, salt and sugar content, and pH levels were entered into the blockchain. Tracking this information helped Sweetgreen get the tomatoes into customers’ salads when they were at their best and reduced waste from spoilage.

Hara is an Indonesia-based agriculture-focused data exchange that brings together data from multiple sources and facilitates data access for banks, insurance companies, retailers, agriculture input suppliers, NGOs, and government agencies. One of the many benefits of having so many different types of data related to agriculture on a decentralized data exchange is that it enables improved access to funding for farmers, which in turn helps them to buy seed and other inputs to increase their production.”

5. Access to Capital

Smallholder farmers around the world struggle to access funding through traditional financial models, like loans. Lack of significant credit histories, land ownership documentation, and other issues make it difficult to access bank loans, so small farmers are often forced to borrow funds from money lenders, at significantly higher rates if the option is even available. Tech savvy agricultural entrepreneurs are now using blockchain to create investment tokens and raise funds for their agricultural businesses.

In Mexico, Agrocoin has created an investment token to enable investors at all levels to support agribusinesses across the Americas. Their first offering funded was a token backed by a square meter of habaneros being grown by Amar Hidroponia in Quintana Roo, south of Cancun.

On the other side of the world, Bananacoin was founded by a team of Russian entrepreneurs in Ventiane Province, Laos. They created the token to raise funds to increase the size of the Bananacoin plantation, where they grow Lady Finger bananas for export to China.

6. Payments

While there is much more to blockchain than just cryptocurrency, payments are still a critical issue for small farms and other businesses in agriculture.

BitPesa was founded in Nairobi in 2013 by former banker Elizabeth Rossiello and was the first company based on blockchain to be recognized by the UK Financial Conduct Authority. Users can make same-day payments to employees, distributors or suppliers into their local or international bank accounts, as well as accept payment from local customers in seven major African currencies. The automated platform allows BitPesa to charge a fee that is a fraction of traditional payment transfers. This improves profitability for farmers and everyone else along the supply chain.

San Francisco based Veem is used by Las Vegas-based online tea distributor Tealet to pay more than 30 different farmers and suppliers in different countries across Africa and Asia. Tealet founder Elyse Peterson has spoken extensively about how her frustration with fees as high as 12% and long clearing times, sometimes five days or longer, for international payments led her to work with Veem. The Veem automated platform uses blockchain to convert payments from the source currency and then into the local currency in more than 80 receiving countries, including China. International payments are processed and available to vendors in one to three days, with a 1.9% fee.

— — —

Most of the initiatives named above are actually addressing several different challenges. There are many more that use blockchain technology in ways that focus on these and other issues in the food and agriculture supply chain. Some companies have blockchain-enabled initiatives that can be used in agriculture but also have wider uses. Whatever the industry, people working in the field or the end consumers may not know that blockchain technology is being used or how it works, just as many internet users don’t know the technology behind the internet or how it works. While the term blockchain is being used widely to attract attention and investors, more important than whether or not a company uses blockchain is whether using blockchain effectively addresses an existing problem — and if the company can deliver on the expectations they are creating.